St. Thomas Aquinas – "Devoured" by the Holy Mysteries

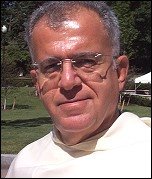

Originally posted here. The following homily was given by Archbishop Augustine DiNoia, O.P., Secretary of the Congregation of Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington on January 27, 2011.

Consumed by the Holy Mysteries of this Great Sacrament

In his premiere biography of St. Thomas, Gugliemo di Tocco wrote of the saint that “he celebrated Mass every day, his health permitting, and afterward attended a second Mass celebrated by one of the friars or some other priest, and very often served at the altar. Frequently during the Mass, he was literally overcome by an emotion so powerful that he was reduced to tears, for he was consumed by the holy mysteries of this great sacrament and strengthened by their offering.”

“Consumed by the holy mysteries of this great sacrament.” The Italian term here is divorato-devoured, eaten up, consumed-by the mysteries.

Surely Tocco’s vivid description of Aquinas’s devotion at Mass stops us dead in our tracks-we, whose celebration of or participation in the Holy Mass is frequently distracted or routinized or just bored. We’re tempted to excuse ourselves with observations like “well, of course, Aquinas was a saint, and this is typically saintly behavior,” or “as a very smart theologian, Aquinas had a more penetrating grasp of things than we do.” But instead of these evasions, what we should do is ask ourselves: what I am missing?

Rare indeed are the mysteries that consume or devour our jaded sensibilities. Perhaps a really good thriller might do so on occasion. But we assume that holy mysteries will be something very different from murder mysteries or natural mysteries.

But we shouldn’t exaggerate the contrast between holy mysteries and other sorts of mysteries. In ordinary usage, the word “mystery” refers to something that remains as yet unexplained or something that is basically inexplicable. We expect the mystery to be resolved in the final pages of a thriller, but at the same time scientists speak of the enduring mysteries of the universe. These kinds of mysteries are not unlike holy mysteries in that, in both cases, our capacity to understand or penetrate a particular reality is challenged in a significant way.

The crucial difference between the Catholic and common uses of the word “mystery” lies here. When the term is applied to divine realities, the mystery involved is by definition without end. This is not to say (as nominalists, in contrast to Aquinas, seemed to want to say) that the things of God are permanently or radically incomprehensible and ineffable, but that they are endlessly comprehensible and expressible. Not darkness, but too much light is what we encounter here. That irritating conversation stopper, “it’s a mystery,” doesn’t mean that we have nothing further to say but that we can’t say enough about the matter in hand. The mysteries of faith are so far-reaching in their meaning and so breathtaking in their beauty that they possess a limitless-that is to say, literally an unending and inexhaustible-power to attract and transform the minds and hearts, the individual and communal lives, in which they are pondered, digested, and, ultimately, loved and adored.

Not for nothing can we use the word in the singular and in the plural, mystery and mysteries. The all-encompassing mystery-in the singular-is nothing less than and nothing else but God himself, and the mysteries-plural-are its many facets as we come to know them.

St. Thomas insistently taught that the mystery of faith is radically singular because the triune God who is at its center is one in being and in activity, and comprehends in one act of omniscience the fullness of his truth and wisdom. Through the infused gift of faith-thus called a theological virtue-the believer is rendered capable of a participation in this divine vision, but always and only according to human ways of knowing. We truly know God, but not in the way that he knows himself. According to Aquinas, the human comprehension of the singular mystery of divine truth is necessarily plural in its structure.

In this sense, we can speak both of the mystery of faith-referring to the reality of the one triune God who is know through the act of faith-and of the mysteries of faith-referring to our way of knowing in the Church the various elements of the singular mystery of God. All the mysteries of our faith point us to the single mystery at their center, nothing else but God himself, one and three.

Coming to the center of this mystery, we affirm with astonished delight the divine desire to share the communion of Trinitarian life with human beings, with us. No one has ever desired anything more. God himself has revealed to us (how else could we have known it?) that this divine desire-properly speaking, intention and plan-is at the basis of everything else: creation itself, the incarnation of the Word, our redemption through the passion, death and resurrection of Christ, our sanctification and glory through the power of the Holy Spirit. Thus St. Paul speaks to us today of the grace he received precisely “to bring to light for all what is the plan of the mystery hidden from ages past in God who created all things, so that the manifold wisdom of God might now be made known through the Church.”

Amazingly, then, it turns out that the divine mystery is the key to all other mysteries. Far from being opaque, it throws light on everything else. To see everything with the eyes of faith-to adopt, as it were, a “God’s eye view”-is to see and to understand everything in the light of this divine plan, “to bring to light for all what is the plan of the mystery.”

Glory, bliss, beatitude-these wonderful terms refer to the consummation of our participation in the communion of Trinitarian life already begun in Baptism, nothing less than seeing God face to face. At the heart of the mystery and the mysteries, finally, is the mystery of divine love. The Catholic tradition has not hesitated to call this participation in the divine life a true friendship with God.

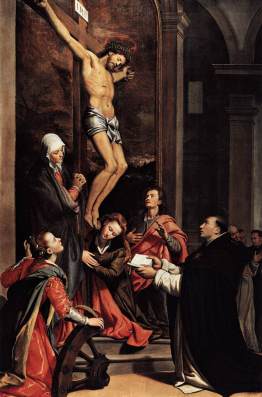

Given all this, was it not fitting that God should be moved to send his own Son into the world and, in the exquisite divine condescension of the Incarnation, to take on a human nature so that he could be known and loved by us as Jesus of Nazareth, Christ and Lord? Was it not fitting that the Son of Man should offer his life to the Father on the Cross in a sacrifice of love for our reconciliation? Was it not fitting that Christ should remain with us in the Eucharist?

Aquinas teaches us to regard these mysteries in the light of the overarching mystery of the divine love. This is very clear in what he wrote about the final question: “It is a law of friendship that friends should want to be together….Christ does not leave us without his physical presence on our pilgrimage, but he unites us to himself in the sacrament in the reality of his body and his blood” (STh 3a, 75, 1).

At the start we asked ourselves: what are we missing? what does it mean to be “consumed by the holy mysteries of this great sacrament”? The answer is really very simple. It means: to be consumed by the love they embody and reveal. Is it any wonder that Aquinas wept in the contemplation of these holy mysteries?

May this great saint, who experienced such rapture whenever he celebrated the Eucharist, help us not to miss being consumed by the love of our divine friends who give themselves to us in this great sacrament, to their eternal glory and to our unending benefit, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Abp. DiNoia on "Why Catholics Go to Mass"

Archbishop J. Augustine Di Noia, O.P.

Secretary, Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments

Introduction

Why get out of bed in the morning? Why eat breakfast? Why sleep seven to eight hours a night? Why run six miles a day? And so on. These activities are so much part of the fabric of everyday life that asking why we perform them seems almost pointless. The answers are self-evident.

Another reason not to think about these questions is that the answers are too complicated. There are too many reasons for doing these things.

The question “why do Catholics go to Mass?” is not unlike these sorts of questions. The answer is obvious. That’s what we do. We go to Mass on Sundays and, if we can, other days too. Why? For lots of reasons.

But sometimes it is a good thing to ponder the supposedly obvious answers to questions like these. In any case, the John Carroll Society asked me to take on the question “why do Catholics go to Mass?” I hope you will forgive me if, in the short time allotted to me, I give only some of the reasons.

Communion with the Blessed Trinity

Let me provide the first and most important reason in the words of Pope Benedict: “The Sacrament of Charity, the Holy Eucharist is the gift that Jesus Christ makes of himself, thus revealing to us God’s infinite love for every man and woman” (Sacramentum Caritatis §1).

The Holy Father continues: “The Eucharist reveals the loving plan that guides all of salvation history (cf. Eph 1:10; 3:8-11)” (ibid. §8). The triune God desires to share the communion of trinitarian life with us, with creaturely persons.

No one has ever desired anything more than the triune God desires this, and nothing makes sense apart from this. Christ himself has revealed to us (for how could we otherwise have known about it?) that “God is a perfect communion of love between Father, Son and Holy Spirit” (ibid.) and that his desire to make room for us in his own communion of life lies at the basis of everything: creation, incarnation, redemption, sanctification and glory.

Through the Mass we begin to see—indeed to experience—everything in the light of this divine intention to share the communion of trinitarian life with us. Looking at things this way—looking at them the way that Christ himself has taught us to do—we understand why we were created, why the Word became flesh, why Christ died and rose from the dead, how the Holy Spirit makes us holy, and why we will see God face to face. We were created so that God could share his life with us. God sent his only-begotten Son to save us from the sins that would have made it impossible for us to share in this life. Christ died for this, and, rising from the dead, gave us new life. To become holy is to be transformed, through the power of the Holy Spirit at work in the Church, into the image of the Son so that we may be adopted as sons and daughters of the Father. Glory is the consummation of our participation in the communion of the triune God—nothing less than seeing God face to face.

“In creation itself, man was called to have some share in God’s breath of life (cf. Gen.2:7). But it is in Christ, dead and risen, and in the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, given without measure (cf. Jn 3:34), that we have become sharers in God’s inmost life” (ibid.).

For this reason, “in the Eucharist Jesus does not give us a ‘thing,’ but himself. He offers his own body and pours out his own blood. He thus gives us the totality of his life and reveals the ultimate origin of this love. He is the eternal Son, given to us by the Father….In the bread and wine under whose appearances Christ gives himself to us in the paschal meal (cf. Lk 22-14-20; 1 Cor 11:23.26), God’s whole life encounters us and is sacramentally shared with us” (ibid.).

This is the most important reason why we go to Mass. But we might well be tempted to ask ourselves, and we should not shrink from doing so: how can Christ make himself present to us in this way? How can this be possible?

According to St. John’s Gospel, the first people to hear Christ proclaim the Eucharist asked exactly that question. Some embraced our Lord’s words in faith, but others were put off by it. When they heard Christ say: “I am the living bread that came down from heaven. Whoever eats of this bread will live forever; and the bread that I will give for the life of the world is my flesh,” they asked, incredulously, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” (John 6:51-52).

How can this be indeed?—a perfectly natural question from the human point of view, the sort of question frequently voiced when people hear about something that God is said to have done or to be doing.

But suppose that we adopt Christ’s point of view. Suppose that instead of maintaining a human point of view we adopt his. When we do this, we may find that our troubling “how can this be?” becomes an awestruck and faith-filled “why not?”

We have seen that God desires to share his life with us in the most intimate manner. The Catholic tradition has not hesitated to describe this participation in the divine life as a true friendship with God. Given this truth of our faith, is it not in a sense appropriate that God should be moved to send his only-begotten Son into the world and, in the breathtaking divine condescension of the incarnation, to take up a human existence to be known and loved among us as Jesus of Nazareth? Was it not fitting, as the Scriptures say, that the Son of Man should offer his life to his Father on the Cross in a reconciling sacrifice of love for our sake?

For St. Thomas Aquinas it is but a short step from the Incarnation to the Holy Eucharist. In this connection, St. Thomas wrote: “It is a law of friendship that friends should live together….Christ has not left us without his bodily presence on our pilgrimage, but he joins us to himself in this sacrament in the reality of his body and blood” (Summa Theologiae III, 75, 1). In effect, Aquinas is saying that it makes sense, given what we know about God’s plan to bring us into the intimacy of his divine life, to leave us the extraordinary gift of the real and substantial presence of his Son in the Eucharist. In the light of the entire mystery of faith, we can see the Eucharist as the gesture of our divine friend. Pope John Paul II wrote in Ecclesia de Eucharistia: “It is pleasant to spend time with him, to lie close to his breast like the Beloved Disciple (cf. Jn 13:25) and to feel the infinite love present in his heart” (§25).

Pope Benedict has said the same thing: “In the sacrament of the altar, the Lord meets us, men and women created in God’s image and likeness (cf. Gen 1:27), and becomes our companion” (Sacramentum Caritatis §1)

But there is more. This is a friendship that expressed itself in the ultimate sacrifice of love in which Christ gave his body and blood up for our sake. When he instituted the Eucharist at the Last Supper, according to Pope John Paul, “Jesus did not simply state that what he was giving them to eat and drink was his body and blood; he also expressed its sacrificial meaning and made sacramentally present his sacrifice which would soon be offered on the Cross for the salvation of all” (Ecclesia de Eucharistia, §12). By overcoming the effects of sin, the sacrificial passion and death of Christ and his glorious resurrection—the Paschal mystery—restored our friendship with God. In this connection, Pope John Paul made a striking point: “This sacrifice is so decisive for the salvation of the human race that Jesus Christ offered it and returned to the Father only after he had left us a means of sharing in it as if we had been present there” (Ecclesia de Eucharistia, § 1). Not only does our divine friend want to stay with us; he wants to do so precisely in virtue of the power of the Paschal mystery which guarantees what must now, always and everywhere, be a reconciled friendship won at the price of his blood.

No wonder that Pope John Paul II could write: “I want once more to recall this truth and to join you, my dear brothers and sisters, in adoration before this mystery: a great mystery, a mystery of mercy. What more could Jesus have done for us? Truly, in the Eucharist, he shows us a love which goes ‘to the end’ (cf. Jn 13:1), a love which knows no measure” (Ecclesia de Eucharistia, §11).

Everlasting Life

An extraordinary promise comes from the lips of our Savior: “I am the living bread that came down from heaven; whoever eats this bread will live forever”(Jn 6:51). This is another important reason why we go to Mass, but we have to admit that nothing in our experience prepares us to believe such a promise. On the contrary, our experience seems to teach us the opposite. We know of nothing that lasts forever. Certainly, we know of no food or drink that do not themselves run out in the end, and so could not in themselves be the source of endless life for us. This is the lesson our experience teaches us, and it is one that we learn very early in life.

Remember when we were children. In the center of the dining room table, there is a scrumptious homemade apple pie from which we have each received a slice but which is not big enough to provide seconds for all of us. We think to ourselves: whoever devours his first portion in the quickest time has the best chance at getting a second. We thought this as children, and we think it still. The lesson is clear: if nothing—and certainly no food or drink—lasts forever, and if we are not to be left with nothing in the end, we must be work hard at acquiring what we need to survive and, indeed, to flourish.

It is all the more remarkable that Christ would use bread and wine as the sign that contradicts our ordinary experience at the same time that it transforms it. Christ takes up perishable bread and wine to signify the imperishable food which is his most holy Body and Blood, and which is the source of the unending life that no ordinary bread and wine can ensure and that only a divine gift can provide.

The miracle of the feeding of the multitude provides us with some insight into this mystery. From five loaves and two fishes, our Lord feeds five thousand people. We learn from the Gospel that, even after the hungry crowd has been satisfied by this miraculous multiplication, the disciples are nonetheless able to gather up leftovers. What does this super-abundance signify? Surely, that Christ could have fed five thousand more, and, indeed, an indefinite number of people. Why? Because he is an inexhaustible source of food. There is no bottom of the barrel here. The Church has rightly seen in this wonderful miracle a sign of the Eucharist in which we receive, not loaves and fishes, but the very Body and Blood of Christ in sacramental form. Recall the verse of the Lauda Sion: “Thousands are, as one, receivers, / One, as thousands of believers, / Eats of him who cannot waste.” The food and drink which Christ gives to us can be the source of unending life because it is itself his inexhaustible Body and Blood. Only this great gift can finally allay our anxiety that, in the end, there may not be enough for us. In Christ, there is enough, and more than enough.

For it is nothing less than the unending divine life which Christ shares with us in the Eucharist: “whoever eats this bread will live forever.” The “heavenly banquet in which Christ is received, the memory of his passion is renewed, and the soul is filled with grace” is a participation in the divine life itself and an intensification of our communion with the Father, Son and Holy Spirit and with one another in them. As we sing in the Pange Lingua: “Faith alone which is unshaken / Shows pure hearts the mystery.” Only faith can overcome our doubts and anxiety, only conversion and repentance can open our hearts to Christ’s promise that “whoever eats this bread will live forever.”

Becoming the Body of Christ

Another important reason why we go to Mass is this: through the Mass we become the Body of Christ. For the Eucharist is the Body of Christ and that the Church is the Body of Christ.

It is from St. Paul that the Church first learned to speak this way. “The bread that we break, is it not a participation in the body of Christ? Because the loaf of bread is one, we, though many, are one body, for we all partake of the one loaf” (1 Cor 10:16-17). About this, St. John Chrysostom’s wrote: “For what is the bread? It is the body of Christ. And what do those who receive it become? The Body of Christ – not many bodies but one body. For as bread is completely one, though made up of many grains of wheat, and these, albeit unseen, remain nonetheless present in such a way that their difference is not apparent since they have been made a perfect whole, so too are we mutually joined to one another and together united with Christ” (Homilies on I Corinthians, 24,2).

The truth is that the eucharistic Body of Christ is source of the mystical Body of Christ. We who receive the eucharistic Body of Christ during Mass become the Mystical Body of Christ. In the terms of St. John Chrysostom’s analogy, just as many individual grains of wheat go together to make the bread that becomes Christ’s body, so the Church is made up of all those individual persons who are united to Christ and to one another in Him. The Church is nothing other than the Mystical Body of Christ that is initiated by the sacrament of Baptism and continually built up by the participation of its members in the eucharistic Body of Christ. Pope John Paul II sought to capture this profound truth by entitling his encyclical Ecclesia de Eucaristia: “the Church from or out of the Eucharist.”

The Mystical Body of Christ is a spiritual reality. The adjective “mystical” is not intended to suggest a contrast with “real,” as when we speak of the “real presence” of Christ in the Eucharist. The Church speaks of the presence of Christ under the appearances of bread and wine as real “not to exclude the idea that others are ‘real’ too, but rather to indicate presence par excellence, because it is substantial and through it Christ becomes present whole and entire, God and man” (Paul VI, Mysterium Fidei, §39). The Church is called the “mystical” Body of Christ because its members are joined not in a physical manner, but in a spiritual union in and with Christ which, though invisible, is nonetheless real.

The Holy Spirit is active in constituting both the eucharistic Body of Christ and the mystical Body of Christ. The prayers of the eucharistic liturgy makes this clear. Take the third Eucharistic Prayer for example. Before the consecration of the Mass, the priest offers an invocation (called the epiclesis) in which he prays: “Let your Spirit come upon these gifts to make them holy, so that they may become for us the body and blood of our Lord, Jesus Christ.” After the consecration, the priest offers a parallel prayer: “May all of us who share in the body and blood of Christ be brought together in unity by the Holy Spirit.” It is through the power of the Holy Spirit that the bread and wine are transformed into the eucharistic Body of Christ, and, furthermore, that we are joined together to form the Mystical Body of Christ.

To grasp that the Eucharist is the Body of Christ and the Church is the Body of Christ, brings us back to where we started: the Blessed Trinity.

If you pass close attention to all of the prayers at Mass, you will notice some intriguingly beautiful patterns. The invocations of the Holy Spirit in the Eucharistic Prayers, like those quoted above, are themselves always set within the context of a larger prayer addressed to the Father. The context is always a trinitarian one, with the Father, Son and Holy Spirit being mentioned in turn and in a certain order that reflects the deepest structures of the economy of salvation itself. The Father sends the Son, and the Father and the Son together send the Holy Spirit. Where? To us. Why? So that the Holy Spirit can return us through the Son to the Father. In other words, the goal is to bring us into a life of communion (aka: friendship!) with the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, and with one another in them.

The key moment in this remarkable movement of the Blessed Trinity towards and into us, and of ourselves towards and into the Blessed Trinity is our transformation in the image of the Son. In his humanity, Christ not only exemplifies the perfect sonship but also transforms us in his image. Christ, the Head of the Body, causes his transforming grace, above all in the Eucharist, to flow into all of the members of his Body so that they are conformed to him by the power of the Holy Spirit. The Father thus sees and loves in us what he sees and loves in Christ, and our union with them and with one another is achieved. The eucharistic Body of Christ—which we receive at Mass—is at the heart of the mystical Body of Christ—which we become at Mass. Amazing, isn’t it?

I’ve given three of the most important reasons why Catholics go to Mass. Allow me a concluding word on how Eucharistic Adoration prolongs the Mass for us.

Conclusion: Eucharistic Adoration

In his apostolic exhortation, Sacramentum Caritatis—from which I’ve quoted several times in this presentation—Pope Benedict wrote: “ I heartily recommend to the Church’s pastors and to the People of God the practice of eucharistic adoration, both individually and in community….In the Eucharist, the Son of God comes to meet us and desires to become one with us; eucharistic adoration is simply the natural consequence of the eucharistic celebration, which is itself the Church’s supreme act of adoration” (Sacramentum Caritatis, §67, 66).

The Holy Father notes that the “inherent relationship between Mass and adoration of the Blessed Sacrament was not always perceived with sufficient clarity.” He notes at times one hears the objection that argued that “the eucharistic bread was given to us not to be looked at , but to be eaten” (Sacramentum Caritatis, §66).

In order to respond to such objections, just recall that at four important moments during the celebration of the Eucharist, the priest elevates the sacred host and the precious blood of the Lord: first, during the consecration when the priest elevates the sacred host and the chalice containing the precious blood; then at the conclusion of the Eucharistic prayer, the priest raises the host and the chalice together; again, before the distribution of Holy Communion, the priest presents the sacred host and the precious blood to the entire congregation with the words “Behold the Lamb of God…;” and finally, in a more personal moment, each communicant is invited to behold and adore the sacred host just before receiving “the bread of life.”

It is in these significant moments of “elevation” that we must find the roots of Eucharistic exposition and adoration as well as the profound connection between the Eucharistic sacrifice of the Mass and Eucharistic devotion to the Blessed Sacrament. Christ, who was raised up on the cross for our sake, who rose from the dead and ascended to the right of the Father, is raised up again at Mass so that we may look on him and be saved. In the solemn exposition of the Blessed Sacrament, this “being raised up for our sake” is prolonged and extended. In exposition, adoration and benediction of the Blessed Sacrament, we have the contemplative extension or prolongation of the Mass itself.

The Christian faithful who behold, adore and receive Christ in the sacrament of the altar desire to continue, in a more contemplative and protracted manner, to look with love on Christ present in the Blessed Sacrament. It is not that Christ becomes more present to us, as Aquinas points out, but rather it is that we become more present to him. In beholding him exposed to us in the monstrance, our attention is more focused and concentrated. In that sense, we become more present to him.

The Holy Father recommends “a suitable catechesis explaining the importance of this act of worship, which enables the faithful to experience the liturgical celebration more fully and more fruitfully” (Sacramentum Caritatis, §67). In a word, the more we adore Christ in the Eucharist, the more deeply we will understand why Catholics go to Mass.

Saint Pius V

from Friar Blog: Below is an English translation of the homily then Fr. Augustine DiNoia, O.P., preached to the members of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith on their patronal feast in 2004. The Mass celebrated by then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the Prefect of the Congregation.

Imagine the scene: A cold January day in 1566, one saint kneeling at the feet of another in the Sistine Chapel. St. Charles Boromeo begging Michele Ghislieri to accept election as the successor to Pope Pius IV. The normally strong and self-controlled Cardinal Alessandrino (as Ghislieri was known) had burst into tears when St. Charles commanded: “In the name of the Church, pronounce your acceptance, most Holy Father!” “I cannot! I am not worthy,” he kept repeating. At last, Cardinal Boromeo’s ear caught the barely audible words of acceptance, and the Dominican Cardinal Alessandrino became Pope Pius V.

Since arriving in Rome over a decade earlier, the saint had wanted nothing more than to return to the beloved Dominican Friars with whom he had spent his life. At the suggestion of Cardinal Carlo Carafa, Pope Julius III had brought him to Rome to become Commissary General of the Inquisition. When a few years later, Carafa became Pope Paul IV, and Fr. Michele implored the new pope to allow him to return to his convent so that he could “live and die as a Dominican,” Carafa responded by making him a bishop and then a cardinal, saying: “I will bind you with so strong a chain that, even after my death, you will never be free to return to your cloister.” It is no surprise that, as a cardinal and even as pope, Michele Ghislieri strove to be faithful to the Dominican vocation he had first embraced when he was twelve years old.

The young Michele had startled two Dominican Friars who were passing through Bosco (the town of his birth) by asking if he could become one of them. They were so impressed by his answers to their questions that, with the blessing of his parents, they allowed him to travel with them to the priory of Voghera in Lombardy where his vocation could be tested. From the start, the Friars loved the boy. They called him a treasure, for his progress in the spiritual life outstripped his rapid advance in his studies. As a novice in Vegevano, his fellow novices looked upon him as one already far advanced on the road to sanctity – silent, recollected, prudent, yet docile, humble, reverent towards his superiors, and jealously observant of the Dominican rule.

There is no time this morning to recount his activities in his long life as a Dominican, most of it spent in studies, teaching, preaching, and governance. Ordained a priest in Genoa at the age of twenty four, Father Michele was known by his brethren to be the first to kneel before the Blessed Sacrament in the morning, and the last to say farewell at night. As a young professor, he used to say to his students: “The most powerful aid we can bring to this study is the practice of earnest prayer. The more closely the mind is united to God, the richer the stores of light and wisdom that will follow its researches.” His brilliant defense of the faith during the Dominican provincial chapter at Parma in 1543 brought him to the attention of the College of Cardinals, and he was subsequently appointed to the difficult and thankless post of Inquisitor at Como. A few years later, he would be called to Rome to head the Inquisition, and here he remained for the rest of his life.

We cannot enter into the many achievements of his pontificate: his implementation of the reforms of the Council of Trent, especially in the liturgy; his promotion of devotion to the Rosary; and his successful efforts to mobilize the leaders of the nations against the threat of the Turks (of whom it was said that they feared the prayers of the pope more than they feared all the armies of Europe).

Although St. Pius was never able to return to his Dominican cloister, the legacy of St. Dominic remained with him in at least one important respect that is also significant for us and for our work in the Congregation: love of the truth and zeal for souls. His intellectual formation as a Dominican, combined with his long experience as a champion of the faith, gave him a profound awareness of the power of error to contribute to unhappiness and disorder in human life, and thus of the authentically pastoral necessity of proclaiming the full truth of the Catholic faith without compromise. In imitation of this great saint, we must pray for the love and the zeal that form the deepest wellspring for the proclamation of the doctrine of the faith.

The election of Cardinal Alessandrino had not been greeted with much enthusiasm by the people of Rome on that cold January day in 1566 because he was regarded as too severe. At the time, he had prayed: “God grant me the grace to act so that they may grieve more for my death than for my election.” Such was indeed the case when St. Pius V died peacefully in the early hours of the morning on the 1st of May 1572.

On Anglican Unity: “De Lisle’s Dream Come True”

Originally posted on Friar Blog:

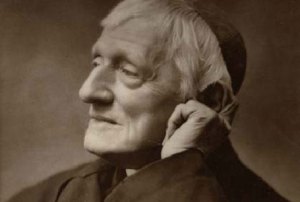

On October 20, 2009, the day on which simultaneous news conferences were held in the Vatican and London, at which the promulgation of a new Apostolic Constitution, Anglicanorum coetibus, was announced, that provides for the reception of members of the Anglican Communion into Full Communion with the Catholic Church in their own “Ordinariates,” Archbishop Augustine DiNoia, O.P., the Secretary of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, asked us to convey to his Dominican brothers and sisters that this was the intention for which he had asked them to pray the “Litany of Dominican Saints” back in February 2009. Archbishop DiNoia has now asked that a remarkable article, written by one of our Dominican confreres in England, the Very Rev. Leon K. Pereira, O.P., the Prior and Pastor at the Priory of the Holy Cross in Leicester, England, be shared with our readers. In this article, it is made clear that the Ven. John Henry Cardinal Newman (to be beatified in 2010) had prayed for such a provision that might allow a greater number of his fellow countrymen to find their way back into Communion with the Holy See. His Holiness, Pope Benedict XVI, a student and devotee of the thought and writings of Cardinal Newman, has been made aware of this article. With the permission of Fr. Pereira, his article follows below.

On October 20, 2009, the day on which simultaneous news conferences were held in the Vatican and London, at which the promulgation of a new Apostolic Constitution, Anglicanorum coetibus, was announced, that provides for the reception of members of the Anglican Communion into Full Communion with the Catholic Church in their own “Ordinariates,” Archbishop Augustine DiNoia, O.P., the Secretary of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, asked us to convey to his Dominican brothers and sisters that this was the intention for which he had asked them to pray the “Litany of Dominican Saints” back in February 2009. Archbishop DiNoia has now asked that a remarkable article, written by one of our Dominican confreres in England, the Very Rev. Leon K. Pereira, O.P., the Prior and Pastor at the Priory of the Holy Cross in Leicester, England, be shared with our readers. In this article, it is made clear that the Ven. John Henry Cardinal Newman (to be beatified in 2010) had prayed for such a provision that might allow a greater number of his fellow countrymen to find their way back into Communion with the Holy See. His Holiness, Pope Benedict XVI, a student and devotee of the thought and writings of Cardinal Newman, has been made aware of this article. With the permission of Fr. Pereira, his article follows below. Two hundred years ago an extraordinary man was born in Leicestershire, Ambrose Philips de Lisle. He was a scion of the ancient De Lisle family, and the founder of Mount St. Bernard’s Abbey. His descendants still come to Mass at Holy Cross. Ambrose de Lisle was a visionary ahead of his time. A convert to the Catholic faith, he dreamed of Christian unity. He wrote a pamphlet in 1876, voicing the idea of a corporate re-union of the Anglican Communion with the Catholic Church, whilst retaining Anglican juridical structures, liturgy and spirituality. When his friend Cardinal John Henry Newman read it, he wrote to him,

“Nothing will rejoice me more than to find that the Holy See considers it safe and promising to sanction some such plan as the Pamphlet suggests. I give my best prayers, such as they are, that some means of drawing to us so many good people, who are now shivering at our gates, may be discovered.”

The plan was doomed to be thwarted in De Lisle’s lifetime. To console him, Newman said:

“It seems to me there must be some divine purpose in it. It often has happened in sacred and in ecclesiastical history, that a thing is in itself good, but the time has not come for it … And thus I reconcile myself to many, many things, and put them into God’s hands. I can quite believe that the conversion of Anglicans may be more thorough and more extended, if it is delayed – and our Lord knows more than we do.”

In our own time, Pope Benedict XVI has rightly been called the ‘Pope of Christian Unity’. Two years ago, the Pope said that in the critical moments of the Church’s history, when divisions arose, the failure to act on the part of Church leaders has helped to allow divisions to form and harden. He observed, ‘This glance at the past imposes an obligation on us today: to make every effort to enable for all those who truly desire unity to remain in that unity or to attain it anew.’

It is with this in mind, no doubt, that Pope Benedict has made this unprecedented and overwhelmingly generous response (N.B. the Pope is responding to a request, not enacting his own initiative) to the many requests submitted to him by Anglicans left in dismay within their own Communion. Already such Anglicans are being castigated as misogynist homophobes – an uncharitable, prejudiced aspersion. Some Anglicans see them as traitors; some Catholics see them as less-than-desirable for our Church.

The real issue is one of unity, genuine unity: that those who seek communion with the Barque of Peter should not be left to founder amidst the waves, but be brought safely aboard where Christ is not asleep, but Master of wind and waves, standing on Peter’s deck. The Pope has shown that real ecumenism is not about courteous disagreement trying to increase each other’s insipidity until one church cannot be distinguished from another in a cosmic-beige mélange. No, the call of the Gospel still holds: one Lord, one Faith, one Baptism. These are our brothers and sisters, shivering at our gates, to be received as brothers and sisters, and not as traitors or second-class Catholics.

The Dominican Order has a small role in all this. On 21 February this year, our brother Fr. Augustine DiNoia, O.P., then Under-secretary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, asked all Dominicans to pray the Litany of Dominican Saints from February 22 (the Feast of the Chair of St Peter) till March 25 (the Solemnity of the Annunciation) for an at-the-time undisclosed intention – it was for this intention. It is no wonder that in our history people have remarked, ‘Beware the Litanies of the Dominicans!’

Fr. Leon Pereira, O.P.

The Power of Prayer

Originally posted here:

“That they may be one” (John 17:21)

“That they may be one” (John 17:21)

Posted by Fr. Brian Mulcahy, O.P. on October 20, 2009

On February 21, 2009, many Dominican priests, brothers, sisters and laity received an e-mail with an urgent prayer request requested by (then) Fr Augustine Di Noia, O.P., Undersecretary of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, asking all Dominicans to pray the Litany of Dominican Saints from February 22 (the Feast of the Chair of St Peter) through March 25 (the Solemnity of the Annunciation) for an at-the-time undisclosed intention. Today, we received an e-mail from Archbishop Augustine Di Noia, O.P., the Secretary of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, with the following announcement:

“Today there was announced — at press conferences in Rome and London — the forthcoming publication of an apostolic constitution in which the Holy Father allows for the creation of personal ordinariates for groups of Anglicans in different parts of the world who are seeking full communion with the Catholic Church. The canonical structure of the personal ordinariate will permit this corporate reunion while at the same time providing for retention of elements of Anglican liturgy and spirituality.

When I asked the friars (and other OPs – Ed.) to pray the Dominican litany from 22 February to 25 March earlier this year, the intention was that this proposal would receive the approval of the cardinal members of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith which was necessary if the proposal of some structure allowing for corporate reunion was to go forward. Our prayers at that time were answered, and now that the proposal has become a reality we can tell everyone what we were praying for then.

Fraternally,

+Abp. J Augustine Di Noia, OP

This momentous news has already hit both the secular and Catholic press, but Archbishop Di Noia wanted all of you to know that your prayers were very effective, and that he extends his most profound fraternal thanks.

New Bridge Over the Tiber

At a Holy See press conference this morning, Cardinal Levada, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, and Archbishop Di Noia O.P., secretary of the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, made a stunning announcement regarding the fruit of ecumenical efforts reuniting the Anglican Communion with Rome. Presenting a “note” they explained a forthcoming Apostolic Constitution defining a new legal structure–Personal Ordinariate–by which Anglican clergy and faithful can reunite with the Roman Catholic Church. Cardinal Levada explained “with the preparation of an Apostolic Constitution, the Catholic Church is responding to the many requests that have been submitted to the Holy See from groups of Anglican clergy and faithful in different parts of the world who wish to enter into full visible communion”.

An “apostolic constitution” is the form of document used by the Holy See to make the most significant canonical and disciplinary provisions for the Church. It is not, then, a simple “decree” (1983 CIC 29 etc), say, or an “instruction” (1983 CIC 34).

The establishment of a “personal ordinariate” will be something of an innovation in modern canon law, although this ordinariate is apparently going to be similar to “personal arch/dioceses” such as those used for the military (1983 CIC 368 and ap. con. Spirituali militum), or to personal prelatures (1983 CIC 294-297), with Opus Dei being the only example thereof to date. One wonders, though, why both of these structures were apparently found to be inadequate for the reception of Anglicans, and why a third way was invented? We’ll have to see. [from Canon Lawyer Ed Peters]

Archbishop Augustine DiNoia, who helped draft the new structure in his former capacity as under-secretary of the CDF, said: “We’ve been praying for unity for 40 years. Prayers are being answered in ways we did not anticipate and the Holy See cannot not respond to this movement of the Holy Spirit for those who wish communion and whose tradition is to be valued.” He said there has been a “tremendous shift” in the ecumenical movement and “these possibilities weren’t seen as they are now.” He rejected accusations that the new Anglicans be described as dissenters. “Rather they are assenting to the movement of the Holy Spirit to be in union with Peter, with the Catholic Church,” he said. Technical details still need to be worked out, and these Personal Ordinariates may vary in their final form, Archbishop DiNoia said. Full details of the Apostolic Constitution will be released in a few weeks but today’s press conference went ahead because it had been planned sometime ago.

Cardinal Levada stated “It is the hope of the Holy Father, Pope Benedict XVI, that the Anglican clergy and faithful who desire union with the Catholic Church will find in this canonical structure the opportunity to preserve those Anglican traditions precious to them and consistent with the Catholic faith. Insofar as these traditions express in a distinctive way the faith that is held in common, they are a gift to be shared in the wider Church. The unity of the Church does not require a uniformity that ignores cultural diversity, as the history of Christianity shows. Moreover, the many diverse traditions present in the Catholic Church today are all rooted in the principle articulated by St. Paul in his letter to the Ephesians: ‘There is one Lord, one faith, one baptism.’”

Meanwhile in London…Catholic Archbishop Vincent Nichols of Westminster and Anglican Archbishop Rowan Williams of Canterbury affirmed that the announcement of the Apostolic Constitution “brings to an end a period of uncertainty for such groups who have nurtured hopes of new ways of embracing unity with the Catholic Church. It will now be up to those who have made requests to the Holy See to respond to the Apostolic Constitution”, which is a “consequence of ecumenical dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion. “With God’s grace and prayer we are determined that our on-going mutual commitment and consultation on these and other matters should continue to be strengthened. Locally, in the spirit of IARCCUM, we look forward to building on the pattern of shared meetings between the Catholic Bishops Conference of England and Wales and the Church of England’s House of Bishops with a focus on our common mission”.

“The on-going official dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Anglican Communion provides the basis for our continuing co-operation”, the declaration adds. “The Anglican Roman Catholic International Commission (ARCIC) and International Anglican Roman Catholic Commission for Unity and Mission (IARCCUM) agreements make clear the path we will follow together.

It’s Official: Dominican Augustine DiNoia to Head the Congregation for Divine Worship

Fr. Augustine DiNoia, OP, a Bronx native, has been named Secretary for the Congregation of Divine Worship and will be elevated to the rank of Archbishop. Well respected for his work as executive director of the Secretariat for Doctrine and Pastoral Practices for the US National Conference of Catholic Bishops (NCCB) from 1993 to 2001, the ‘then’ Cardinal Ratzinger called him to the Eternal City to work as his undersecretary at the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. He was appointed by Pope John Paul II in April, 2002.

Fr. DiNoia is a a prolific writer, editor, professor and brilliant theologian who is purported to have ghost-written Redemptionis Sacramentum (On certain matters to be observed or to be avoided regarding the Most Holy Eucharist). Speculation continues as to why Pope Benedict replaced his favored Archbishop Malcolm Ranjith with Fr. DiNoia. Rather than appointing a known ‘liturgist’, Pope Benedict would seem to be emphasizing the theological heart of worship by the selection of his trusted collaborator. The Holy Father has written extensively on the theology of the liturgy and the organic continuity of worship, a topic near and dear to his heart. At a time when the English re-translation of the Roman Missal is being finalized and the murmurs of something historic brewing on the Anglo-Catholic front, a theologian of DiNoia’s acumen appears inspired.

Theology of the liturgy means that God acts through Christ in the liturgy and that we cannot act but through Him and with Him. Of ourselves, we cannot construct the way to God. This way does not open up unless God Himself becomes the way. And again, the ways of man which do not lead to God are non-ways. Theology of the liturgy means furthermore that in the liturgy, the Logos Himself speaks to us; and not only does He speak, He comes with His Body, and His Soul, His Flesh and His Blood, His Divinity and His Humanity, in order to unite us to Himself, to make of us one single “body.” In the Christian liturgy, the whole history of salvation, even more, the whole history of human searching for God is present, assumed and brought to its goal. The Christian liturgy is a cosmic liturgy – it embraces the whole of creation which “awaits with impatience the revelation of the sons of God” (Rom. 8; 9)…The liturgy derives its greatness from what it is, not from what we make of it.

Cardinal Ratzinger on the Liturgy

Fr. DiNoia, OP to Head Congregation for Divine Worship?

The rumor mill is churning but it looks like Dominican father Augustine DiNoia, OP will move from the number 3 position (undersecretary) in the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (formerly headed by Cardinal Ratzinger) to the number 2 position in the Congregation for Divine Worship. Considering this Congregation is responsible for the re-translation of the Mass for English speaking countries it makes sense that Pope Benedict XVI would select DiNoia, his trusted advisor, to take the helm as Archbishop. Exciting news for the Church and for my former professor.